Tucked away in Perkasie’s Lenape Park is one of Bucks County’s treasures, a footbridge inspired by the classic designs of John A. Roebling’s Sons & Co. How the two-span suspension bridge came to be involved Perkasie Borough Council, the federal government, and the design skills of a WPA engineer in based in New Britain, Pa.

Posts By Scott Bomboy

How Perkasie Got Its Own Roebling-Style Bridge

In-Person Memories of Old Perkasie

In February 1954, the Perkasie News-Herald published interviews with Borough residents who were alive in 1879, for the upcoming Perkasie Borough 75th anniversary celebration. Each person remembered Perkasie in its Victorian era. And most grew up in Bridgetown or Benjamin, before it became part of Perkasie in 1899. Here are highlights from those interviews.

Feb. 18, 1954: Elmer K. Moyer

The Klan’s Brief Stay in the Perkasie Region

On a recent visit to Perkasie’s Treasure Trove, I found a seemingly innocent paper weight with a link to one of Perkasie’s more controversial stories: the brief presence of the Ku Klux Klan’s regional headquarters on Fifth Street.

The day that Perkasie’s Menlo Park officially opened

On May 30, 1892, Perkasie’s new amusement park, Menlo Park, officially opened to the public. Today, its only remaining attraction is the historic Perkasie Carousel. But Menlo Park, in some form, has been a part of Perkasie’s culture since the Victorian era.

The true meaning of Perkasie’s Memorial Day (or Decoration Day) traditions

The occasion of Memorial Day, or Decoration Day as it was once called, is nearly as old as Perkasie Borough itself. While the holiday as evolved over time, its importance remains with us as a solemn reminder of the price paid for our freedoms.

On May 28, 2022, the 130th Memorial Day parade and service will take place in Perkasie, with the Borough taking a lead role in the event. In past even-numbered years, Perkasie Borough supported the Hartzell-Crouthamel Post #280 of the American Legion. In odd-numbered years, Sellersville Borough and American Legion Post #255 leads the parade program. That tradition started in 1950.

Informal ceremonies to honor the war dead started regionally in America toward the end of the Civil War. Initially called Decoration Day, people made sure the graves of Union and Confederate participants were decorated with flowers on May 30th each year. That was the most-observed date for Memorial Day until 1971, when a federal act moved the federal holiday to the last Monday in May. (Not all states observed the date change and there is still some controversy about it.)

This 1899 photo is likely the annual Decoration Day parade, based on newspaper accounts

Hats off to Perkasie’s Mrs. Johnson

A question came up recently about one of Perkasie’s first businesswomen, and whatever became of Mrs. W. K. Johnson – the Borough’s first French milliner.

It took a little digital detective work to track down Perkasie’s trendsetter of Victorian fashion, but thanks to the Ancestry.com and Newspapers.com websites, we know a lot more about the women’s hat business in Perkasie when hats and bonnets were a big deal in the Borough.

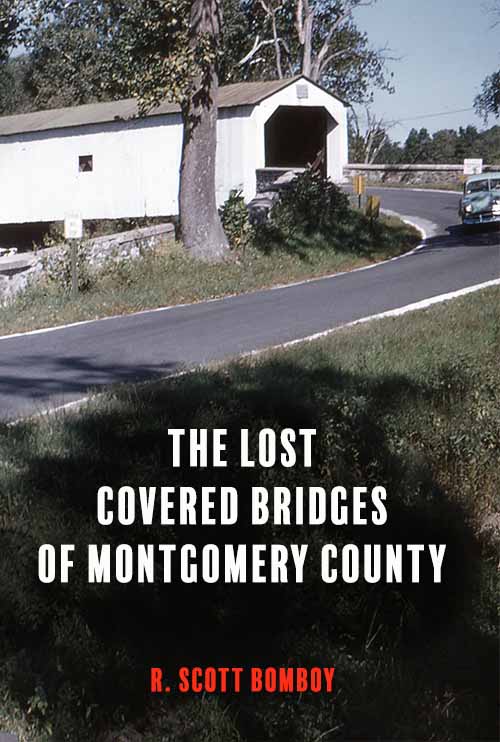

Introduction To Wooden Treasures, the Story of Bucks County’s Covered Bridges

Here is a special preview of my new book “Wooden Treasures: The Story of Bucks County’s Covered Bridges.” The book is about 222 pages long and includes more than 240 images and drawings, with many published publicly for the first time. For more information about the book “Wooden Treasures,” go to coveredbridgebook.com.

Introduction

Dr. Anderson M. Scruggs liked to send poems to the New York Times, which featured reader submissions during the 1930s. Dentistry was Scruggs’ paid profession and he taught it at Atlanta Southern Dental College in Georgia. However, Scruggs loved writing poetry about rural life based on his childhood experiences in West Point, Georgia, a small railroad town on the Chattahoochee River.

Horace King and his family built many of the covered bridges on the Chattahoochee. King was a former slave who gained his freedom from money received from his master and bridge-building partner, John Godwin. King used a bridge design patented by New England architect Ithiel Town, which King adapted for use not only over the Chattahoochee River, but throughout Georgia and Alabama. King and his four sons designed and built more than 100 covered bridges in the South. By 1932, many of King’s covered bridges were disappearing as Georgia’s state highway department demolished them and built steel replacements better suited for motor vehicles. That didn’t stop Anderson from questioning why this was happening to King’s bridges in rural Georgia.

Made in Perkasie by A Pennsylvania Dutchman

When the news broke last week that the old Freed Glass facility in Perkasie would get new life, some deserved attention was focused on a key leader in Perkasie’s growth as a modern town: John Melvin Freed.

Mel Freed started his company in 1920 in his family’s basement in Perkasie on Callowhill Street. The J. Melvin Freed Inc. firm was one of Perkasie’s key employers for decades, and it was one of the critical businesses, along with Snyder Cigars, the Beidler and Royal Pants clothing factories, and the U.S. Gauge plant in Sellersville, that helped Perkasie survive losing its cigar trade and the Great Depression.

Mel Freed started his company in 1920 in his family’s basement in Perkasie on Callowhill Street. The J. Melvin Freed Inc. firm was one of Perkasie’s key employers for decades, and it was one of the critical businesses, along with Snyder Cigars, the Beidler and Royal Pants clothing factories, and the U.S. Gauge plant in Sellersville, that helped Perkasie survive losing its cigar trade and the Great Depression.

Freed was born in East Rockhill Township in 1888. He graduated from Perkasie High School in 1906 as one of six senior class members. By 1910, Freed was living with his parents on Callowhill Street. He then attended and graduated from Muhlenberg College and studied for a year at Cornell University. Over the next few years, Freed moved to Allentown to teach high school biology, but his life would change forever after his brief service overseas in World War I.

Freed’s Army enlistment lasted from December 1917 to July 1919, and included duties at a mobile laboratory unit, the ambulance service, Army medical school, and a field hospital. Freed spent seven months in Europe, which as the hub of the microscopic slide business.

A Newspaper Editor’s Candid Story About the Menlo Pool

In January 1951, Perkasie News-Herald editor John Sprenkel spoke in public about the Menlo Park pool and one of its most controversial policies.

At the time, Menlo Park and its pool were still privately owned. Perkasie Borough would not acquire the facilities until May 1, 1956, and only after Perkasie residents approved the purchase by a 3 to 1 margin in a referendum. Royal Pants owner Maurice Neinken donated $25,000 toward the $115,000 sale price to make sure local children could access the pool.

Sprenkel also knew of the pool’s history, having written about it back in 1939 when first modern pool was built using money gained by Henry Wilson, the park’s owner, from selling part of his land to Perkasie Borough for Lake Lenape Park. The $30,000 pool investment was part of a plan to restore Menlo Park to its glory days in the Victorian era.

Presentation At Pearl Buck International About Her Civil Rights Legacy

Thanks again to everyone who attended Thursday night’s virtual presentation at Pearl Buck International about her civil rights legacy in the 1930s and 1940s.

Here is a link to a PDF of the presentation slides: Pearl Buck’s Civil Rights Legacy

Here is a link to a PDF of the presentation slides: Pearl Buck’s Civil Rights Legacy

Also below is the editorial previewing the event that ran in our local newspapers:

Remembering Pearl Buck’s important civil rights legacy

Author and humanitarian Pearl S. Buck supported many causes during her remarkable life. Among her most important fights was Buck’s early battle to promote civil rights in the 1930s and 1940s.

The Nobel Prize winning author moved to Bucks County, in Hilltown, in 1935. By then, Buck had spoken out publicly on a regular basis against “race prejudice.” Within a decade, Buck’s writings and speeches would be tracked by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Before her return from China in 1934, Buck wrote a moving criticism of American politicians who were blocking anti-lynching laws for Opportunity, the journal of the National Urban League. During the 1930s, Buck’s writing about racial equality appeared mostly in Black-owned newspapers such as the Pittsburgh Courier and the New York Age. Such efforts received few mentions in the mainstream press, which portrayed Buck as an international celebrity, or as a novelty as a popular woman author in America.

By late 1941, Buck’s media image changed when she began criticizing the federal government’s discrimination policy at military subcontractors and its general policy of military segregation. On October 19, 1941, Buck spoke at a regional meeting of Soroptimist clubs at the Doylestown Inn. Her comments were squarely meant for a white audience about the need to end segregation. “I realize it is a touchy problem, but I feel it is important,” she told an audience of 200 people. Buck said she had written to 12 prominent White leaders and media figures asking them to help raise awareness of race prejudice. She had two responses. Columnist Dorothy Thompson joined Buck to meet with Black leaders, while popular radio columnist Raymond Gram Swing refused. There was little or no response from the other 10 people.

A month later, Buck confronted The New York Times in one of the most significant events of her career. On November 12, 1941, the Times editorial page claimed that a recent Harlem stabbing was not a racial problem, but an economic issue to be addressed with more job opportunities for Blacks along with more policing. Buck’s 2,300-word response set off a public debate into December. “Race prejudice and race prejudice alone is the root of the plight of people in greater and lesser Harlems all over our country,” she told the Times. Buck also said prejudice against Black workers in defense industries had to end. A week after the Pearl Harbor attack, Senator Arthur Capper of Kansas had Buck’s letter read into the Congressional Record during hearings about defense sector discrimination. Most importantly, the New York Times gave Buck a frequent platform during the war to write op-eds about racial equality for an international audience.

Buck’s writings also caught the FBI’s attention. Agency reviewers considered her comments about military segregation as “sabotage” and criticized Buck’s connections to what it considered a “Communist front” – the American Civil Liberties Union – which opposed segregation and the government’s internment of Japanese-American citizens. By 1946, the FBI concluded Buck was not a Communist but “all of her activities tend to indicate that she considers herself a champion for the colored races, and she has campaigned vigorously for racial equality.”

By the late 1940s, Pearl Buck’s role as a civil rights advocate changed for several reasons. Buck and her husband Richard Walsh focused on their new adoption agency, Welcome House, which sought to help biracial children. And Buck decided to openly write about her intellectually disabled daughter, Carol, and campaign for more awareness about that group.

That didn’t stop the Washington, D.C. school district from banning Buck from speaking at a segregated public school in early 1951 because she had not been “cleared” by the House Committee on Un-American Activities. Buck told the Perkasie News-Herald the ban was really related to her opposition to school segregation in Washington. Howard University, the NAACP, and local ministers in Washington soon condemned the ban, followed by the Washington Post and numerous newspapers nationally after Buck published her intended speech for Black students at Cardozo High School.

Buck’s importance to the civil rights movement had been well-established by then. Later in the 1950s a young minister sent Buck as personally dedicated copy of his book about the Montgomery Bus Boycott. “To Pearl Buck In appreciation for your genuine good-will, and your great humanitarian concern. With warm regards Martin L King Jr.” King later served on the Welcome House board of directors.

Today, Pearl Buck is known for her efforts at Welcome House and her career as a bestselling author. But her fight for equal rights is an important example we can all learn from – when Pearl Buck spoke out about injustice at the height of her international popularity.

Scott Bomboy is a historian who had written frequently about local and national topics. He will be speaking online for the Pearl Buck International on January 13 about Buck’s civil rights legacy. Registration is required for the free online event at https://pearlsbuck.org/civilrights/.