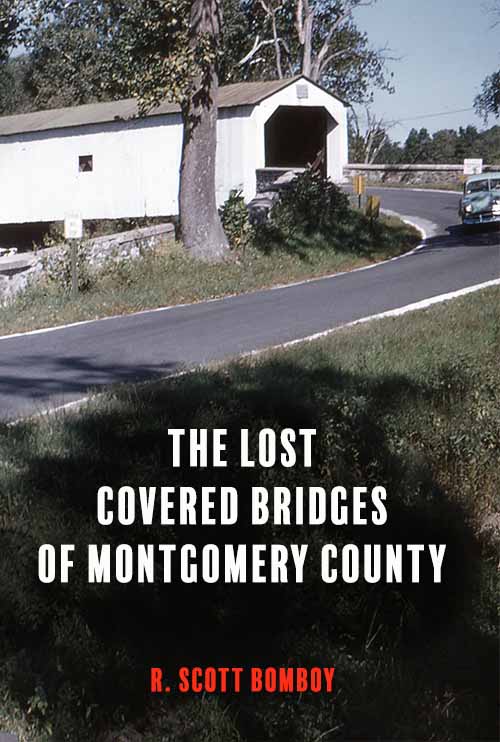

The following is taken from the introduction and conclusion of my new book, “The Lost Covered Bridges of Montgomery County,” now available on Amazon.com.

The chairman of the Lehigh County commissioners, Donald Hoffman, received an unusual letter in 1971 from Robert Rothenberger, the director of Montgomery County’s parks system. Rothenberger was asking for a favor from Commissioner Hoffman: the donation of an intact covered bridge from Lehigh County.

“In Montgomery County at one time there were many covered bridges, however, today there is not even one. As director of parks, I would like to obtain one to show what did exist years ago,” Rothenberger explained. “I am writing to you in the hope that such a covered bridge may exist in a narrow road in your county, or surrounding area, which may be doomed for destruction to make way for wider roads to meet modern traffic patterns,” Rothenberger asked. “The objective would be dismantlement and restoration on one of our county sites where its presence would be justified by tourists or visitor appreciation.”

Commissioner Hoffman declined the request. By the early 1970s, covered bridges attracted tourists and had become a particular point of civic pride in regions where they still existed. Lehigh County had four covered bridges. Montgomery County’s neighbors in Bucks County had 13 covered bridges and Chester County had 15 covered bridges. However, Montgomery County’s commissioners allowed the demolition of their last covered bridge in June 1956, amid much controversy.

In short, politics, money, and Mother Nature led to the gradual extinction of covered bridges in Montgomery County on the Schuylkill River and the county’s main waterways. Unlike in Bucks County and Chester County, Montgomery County’s leaders showed no interest in preserving covered bridges until 1941, and that effort failed after a court battle in the 1950s and a county commissioners’ election in 1955.

At one time, Montgomery County had 36 covered bridges. During the start of the early Industrial era, 14 covered bridges spanned the Schuylkill River at various locations in Montgomery County, from Lower Merion to Pottstown. All of them were privately controlled toll bridges and most were profitable. But all but one became part of a political campaign in the 1880s to free the Schuylkill River from tolls, at great taxpayer expense.

The other 22 covered bridges sat on the Perkiomen Creek and smaller creeks in the interior of Montgomery County. Five bridges were conventional wooden covered bridges. Another nine bridges were unconventional hybrid structures built by railroad companies with timber decks and trusses, covered by sheet metal.

Starting in the early 1900s, new modes of transportation made the wooden structures obsolete. In some cases, government officials replaced the timber structures with concrete and steel bridges. Between 1924 and 1926, four Montgomery County covered bridges also were lost in fires, with three incidents suspected cases of arson. The demolitions sped up when Gifford Pinchot took office as governor in 1931 and promoted an ambitious rural roads program during the Great Depression.

By 1937, only the Markley’s Mill Covered Bridge in Upper Hanover Township remained in Montgomery County. The bridge was seemingly spared twice. In 1941, Montgomery County took the unusual step of taking back the possession of Knight Road from the state, where the bridge sat next to the estate owned by Montgomery County president Judge Harold G. Knight. However, at the start of the Baby Boom, the Philadelphia Suburban Water Company targeted Judge Knight’s farm and the covered bridge for the Green Lane reservoir project.

An agreement was reached in 1955 to take apart and reassemble the Markley’s Mill Covered Bridge in a nearby park. But a bitter court battle over the fate of Knight Road led to the county commissioners allowing the bridge’s demolition, after the Philadelphia Suburban Water Company claimed it lacked funds to relocate the covered bridge.

The demolition of the Markley’s Mill Covered Bridge remains to this day as controversial, since the Philadelphia Suburban Water Company had clearly pledged to relocate and preserve the covered bridge, and then retracted that pledge with no opposition from the Montgomery County commissioners.

Had the timing been different by a few years, Montgomery County may still own a covered bridge. The regional and national movement to preserve covered bridges had just started to gain momentum, mostly in New England, by the late 1930s. By 1957, a regional movement had started to preserve covered bridges in Pennsylvania.

In August 1958, the residents of Perkasie in Bucks County decided to save their covered bridge from a condemnation order from the Bucks County commissioners, amid much local and national publicity. In 1959, the newly formed Theodore Burr Covered Bridge Society of Pennsylvania lobbied the state Department of Highways to adopt a “preservation first” policy for its covered bridges, and it led successful efforts to save the historic Knox Covered Bridge in Valley Forge Park in Chester County and Sheard’s Mill Covered Bridge in Bucks County.

In 1960, the Delaware Valley Protective Association joined residents to save New Jersey’s last covered bridge in Sergeantsville, across the river from Bucks County. The Green Sergeant’s Covered Bridge Association gained the support of a state senator and representative. In June 1960, a superior court judge stopped construction on a new bridge while the covered bridge remained in storage. State highway commissioner Dwight R.G. Palmer brokered a compromise to have both bridges constructed at the same location as one-way bridges.

The Bridgewater Courier-News commented on the Green Sergeant’s Covered Bridge in September 1961. “There are many things in our past which should be preserved. They remind us that our forefathers had their problems and they brought solutions to them. We should not destroy them all in the name of progress.”

“The Lost Bridges of Montgomery County” is available on Amazon.com in print ($22.99) and Kindle ($9.99) versions. The book is 160 pages long and has more than 140 pictures and illustrations. Click here for more information and to order.